Are you upset you can’t play this year?

by Beau McBride

“Are you upset you can’t play this year?” Annie asks me.

This is a question I get asked a lot. Every time, my immediate answer is Yes.

Which is true…sort of.

The Secrets To Staying Sane and Raising Great Athletes

Career-ending injuries are supposed to be tragic

Had my arm stayed healthy, I would be out there with my friends every day, enjoying my last season of High School Baseball. Yet, as time passes, I’m starting to believe my injury happened at just the right time.

This would seem strange, given that my UCL tear severed the relationships I had been building with college coaches and cut short what was supposed to be the culmination of my Higher School career.

Career-ending injuries are supposed to be tragic.

And it was, at first. It started with a sharp pain in my elbow while playing catch with my dad. The doctor said I had a partially torn elbow, with a fifty percent chance of healing if I rested it for two months. So, eight weeks later, I went to throw and had the same sharp pain, tragic.

My baseball career ended long before some ligament wiggled out of place

All those hours and years traveling to random towns in the West suburbs every weekend had been for nothing. I wasn’t going to get a scholarship to play in college, which was supposed to be the reward for enduring the torture of travel ball.

What I didn’t realize is that my baseball career ended long before some ligament in my arm wiggled out of place. As I got into my later years of travel ball, playing for bigger and more established teams each year, I began to hate the whole system. It drained parents’ wallets and dragged middle schoolers across the country to play for pretentious awards like “The 12U USA Summertime Class Third Place Medal.”

I began to see the craziness around me

I was like Winston Smith in 1984—noticing that the system was intended to make people crazy. I began to see the craziness around me: in my coaches, in the parents of the other team’s players, in the parents of my own team’s players, in the scouting directors, and, eventually, in my teammates and in myself.

The game I had learned to play and love in the backyard had been contorted, corrupted, and monopolized so effectively that I had to comply with the system in order to play in college. And that was the plan—I would put up with everything to go to a prestigious college that would never take me for my grades alone, marred as they were by my sub 2.0 sophomore GPA.

My dad and I never acknowledged it, but this was the payoff.

The joy I once felt was gone

I could only sustain myself on such a faulty motivation for so long, however, and soon it got to the point where, on our seventh day at a tournament in Marietta, Georgia, we were hoping my team would lose our playoff game so we could finally go home.

The joy I once felt playing baseball was gone.

By my junior year, although I despised travel ball, I viewed it as a means to college and thus molded myself into the type of player who gets ” written up,” as they say, at showcases. My actual performance suffered.

I will never know if I would have gotten a scholarship to one of my dream schools

College coaches want someone who can throw hard, not good players. The college scout mantra is that a player can be taught to throw strikes. So, I placed all my emphasis on throwing hard, unconcerned with its effect on my actual pitching.

So, as a junior, I was hardly a better pitcher than I was as a freshman—I just threw harder. Yet when I went to showcases over the summer, chucking fastballs over the plate and lighting up guns, I got more attention from college coaches than I ever had before. I was talking to colleges that I had no business talking to, given my grades. It was right in the middle of these talks when my elbow gave out, so I will never know what would have happened, whether I would have gotten a scholarship to one of my dream schools.

I would have felt out of place

Now, I like baseball—it’s fun to play. But my passion is history, reading, and writing—academic stuff. Stuff I never had the time for before.

Had I made it to one of those fancy colleges, I would have felt out of place and not smart enough. I would have needed extra studying, for which I wouldn’t have had the time amidst my workouts, pitching clinics, and team practices every day. Straining merely to pass my required courses.

Being around such academic prestige would have made me want to be a part of it, join clubs, write in the school newspaper, debate with my classmates, and spend my nights in the library reading up on whatever I wanted, yet I wouldn’t be able to, and this conflict would have ripped me apart.

Make me feel like a con man

Using baseball to get in and then quitting the team, especially in the first or second year, would be unprincipled. I wouldn’t be able to bring myself to do it. Even during my junior or senior year, the fact that I accepted money from the school would make me feel like a con for abandoning baseball – that was why I was brought there in the first place.

I would probably wish, every day, for my elbow to tear straight off the bone so I would have a justifiable excuse for retiring. With this mindset, I would most likely be detached from the team, a locker room cancer, as they call it, not because I hold malice towards any of my teammates but because I come to the field every day out of obligation rather than passion. And I would find happiness neither on the field nor in the classroom, as I would be too preoccupied with baseball to infiltrate any communities on campus. I would be alone, torn between two worlds, stuck playing a sport for four years at my “dream school.”

Thank God my elbow tore

So when someone asks me if I’m upset about not being able to play this year, I respond with a yes, but I know time will make my injury less tragic. In four years, at the end of my college journey, wherever that may be, I’ll be saying, “Thank God my elbow tore right before my senior year.”

Annie is unaware of the string of thoughts she just provoked. All she hears is “yes”.

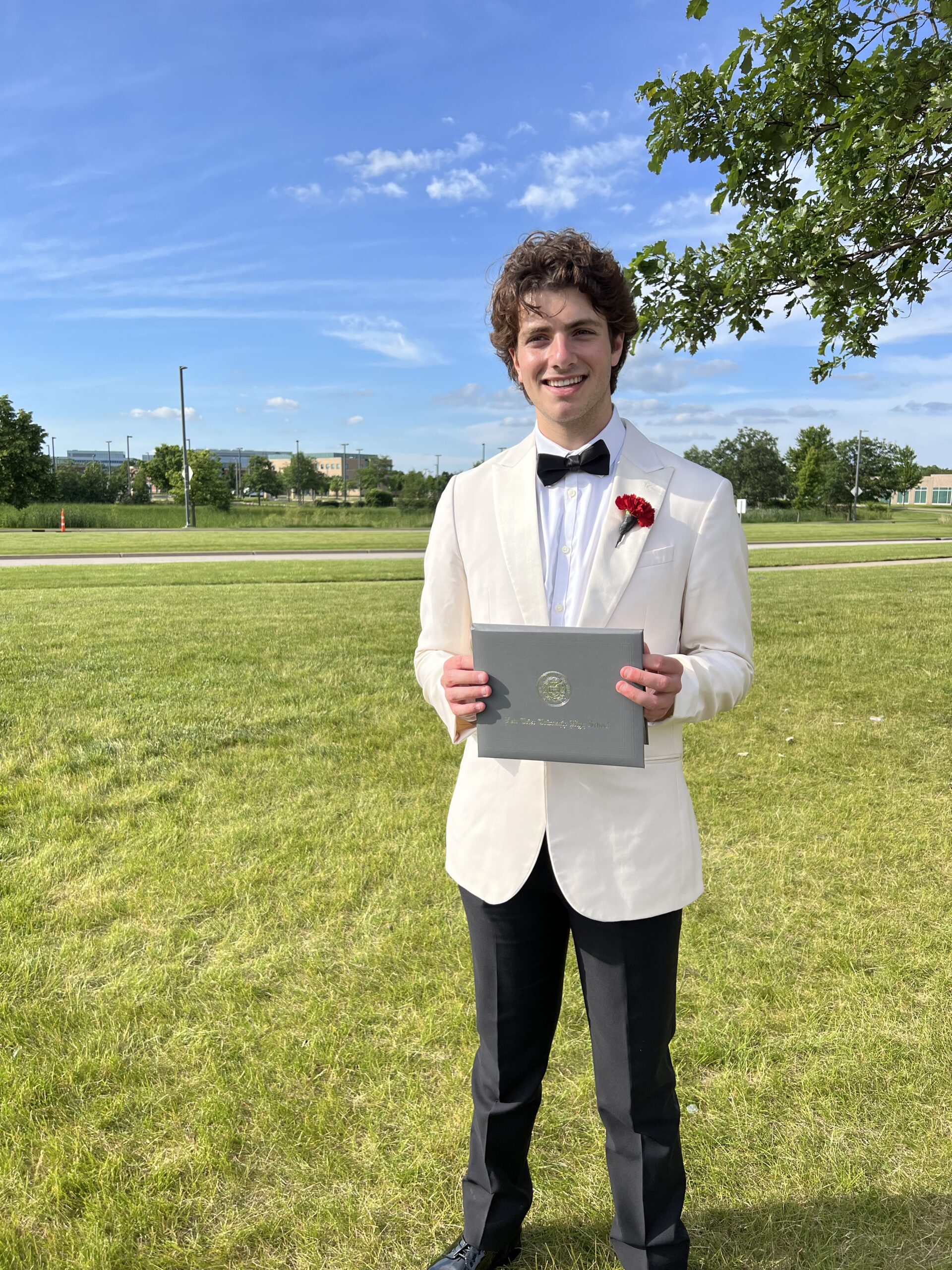

Beau McBride graduated from New Trier High School in 2024 and will attend Indiana University in the Fall, where he plans to major in Political Science. Beau raised his grades above 4.0 GPA his senior year and was a recipient of the English Department Award for Excellence and the Helen Morrow Scholarship for his dedication to social studies.