An NFL Team Doctor’s Argument Against Early Sports Specialization

By Alex Flanagan

These are the new three dirty words in youth athletics, Early Sports Specialization. A term used to describe year-round training in a single sport by kids. It’s a trend often fueled by parents who want to give their child a competitive advantage and one that is growing so quickly medical experts are worried.

Early Sports Specialization has become so prevalent that it now has its own initialisms like other syndromes, disorders and diseases. The medical community calls it ESS–Early Sport Specialization. What most parents don’t know is it no longer applies only to children who focus on one sport. The amount of time dedicated to a sport and whether or not it’s seasonal or year-round are also considerations. Translation… If your child plays basketball, football and is on a year-round baseball team, they likely fall under the ESS umbrella.

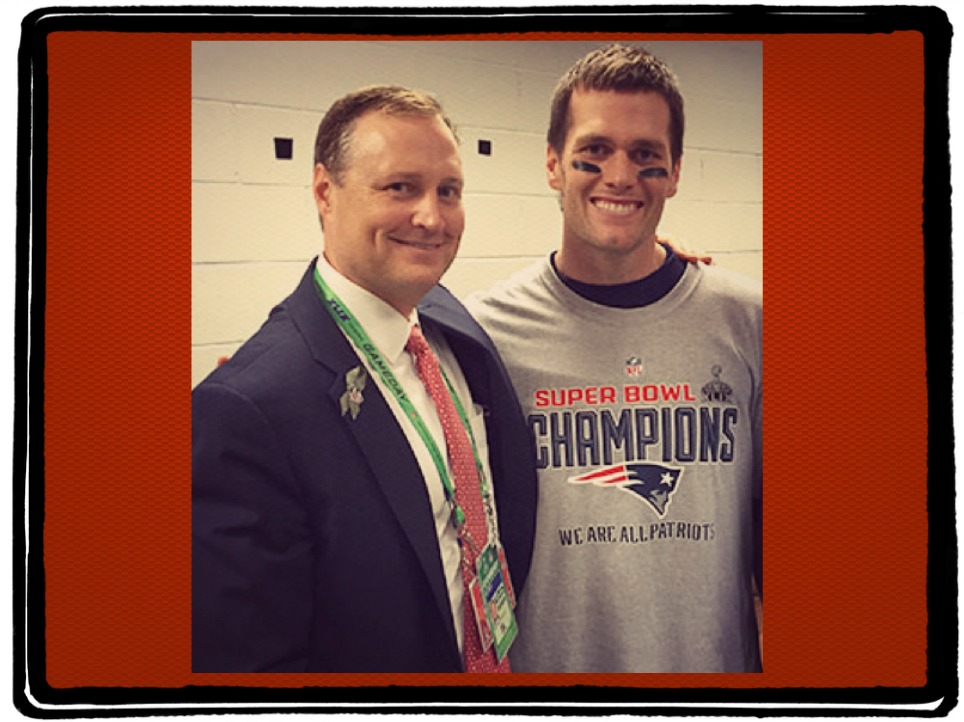

So what does it all mean? I asked the head team physician and Medical Director of the New England Patriots to educate parents on ESS. Along with being the Patriots team Doc, Dr. Matthew T. Provencher is also the Chief of Sports Medicine and Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital and a Visiting Professor at Harvard University. After reading what he has to say below, it is hard to imagine why any of us would ever let our young children “specialize” in sports.

Early Sport Specialization (ESS): What Parents need to know

(By CDR Matthew T. Provencher, MD MC USNR)

Recently, I attended an Early Sport Specialization Forum hosted by American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) with the goals of: Defining the problem of ESS, assembling the experts to discuss the scientific evidence regarding ESS, and, most importantly, The consequences of doing one sport too early and for too long. Representatives from the National College Athletic Association (NCAA), U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC), International Olympic Committee (IOC), American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) were all in attendance.

Early sport specialization (ESS) is defined as the intense, year-round training in a single sport without participation in another sport under the age of approximately 11- 12. HOWEVER, there is a debate regarding what level of activity should be considered “specialization” and what should be regarded as “early.”

Several factors are considered when defining specialization including volume of training and whether or not there is year-round participation and participation in other sports. Ultimately, I believe the most important question to ask is whether or not the young athlete has to significantly alter other sports participation in order to focus on a single sport.

With respect to volume, specialization is set on a continuum. There should be no binary cut-off associated with defining specialization. Instead, specialization should be defined in degrees with correlation to amount of hours per week. “Early” (i.e. what age does the athlete start to focus on a single sport) is also important to define, and varies somewhat by the specific sport.

When discussing how to define “early sport specialization,” a consensus was reached that athletes under age 11-12 who focus on a single sport belong in the “early” and “specialized” categories. It was also noted that some sports might fall outside of this definition, including gymnastics and some forms of ice skating, swimming, and diving, due to the earlier peak age for high-level competition in these sports. However, other sports, like baseball, basketball, and football, all face a similar critical age between the ages of 7 to 8 when year-round participation becomes possible and likely detrimental to long-term success.

Ultimately, the goal of specializing in a sport, for most, is to gain an edge over the rest of the competition and achieve elite status. But before considering if sport specialization does indeed increase the odds of attaining a college scholarship and becoming a professional athlete, the odds of accomplishing said goals should be taken into account.

The statistics are quite humbling – according to a 2010 issue of Current Sports Medicine Reports the typical male high school senior who plays football has a 5.8% chance of becoming a college football player. The typical college senior has a 2% chance of being drafted to the National Football League. All in all, a high school senior who plays football has a 0.09% chance of being drafted by the NFL.

As is evident by the numbers, the chances of ultimately becoming a professional athlete in many sports are remotely small. However, there are some that believe ESS may provide an upper hand over the rest of the competition. But contrary to this notion, studies conducted on ESS have concluded this is not true. Elite athletes in the vast majority of sports who focused on a single sport early in their career had less success than their counterparts who were multi-sport athletes. Specifically, the following studies highlight these findings:

- Elite Russian swimmers who focused solely on swimming before 11 years of age retired earlier and competed for a shorter amount of time at the national level versus swimmers who specialized later on in age.

- Elite athletes in most sports specialized later in age than those that were non-elite athletes. Additionally, non-elites trained more hours during age 9-15 than their elite counterparts.

- 1558 Olympic sport elite and non-elite athletes were surveyed – elite athletes on average began sport specialization later in age. Elite athletes were also more likely to participate in multiple sports after 11 years of age than their non-elite counterparts.

Additionally, a significant body of evidence demonstrates that young athletes who participated in multiple sports have better speed, better gross motor coordination, more explosive strength, and overall, are more physically fit. Even further legitimizing the advantages of participating in multiple sports, previous studies have also confirmed that both professional and world-class athletes were more likely to compete in multiple sports at a young age and also spent more time playing unstructured sports outside of practice and competition during their developing years (ages 5-12 years).

In a study involving 735 boys in three age groups (6-8, 8-10, and 10-12 years), all young athletes underwent a fitness test to determine strength, endurance, speed, and gross motor coordination. Alongside the fitness test, a physical activity questionnaire was administered that allowed researchers to divide all athletes between those who participated in ESS and those who practiced early diversification. Comparisons were made between the groups to determine any differences in physical ability. The data showed that athletes who participated in multiple sports were, on average, faster, stronger, better coordinated, and more physically fit.

Several studies have investigated the effects of ESS versus diversification in regards to performance in future athletic endeavors. In particular, a study determined that young athletes between 11 and 15 years of age, who competed in multiple sports (e.g. men’s and women’s tennis, men’s basketball, Olympic sports, men’s and women’s swimming and others), were more likely to compete at an elite national level in their chosen sport than their single-sport counterpart. Multi-sport athletes ultimately become superior athletes in their chosen sport because they are exposed to a greater variety of physical and cognitive environments during their developing years.

It has also been shown that ESS leads to an increased risk of injury. The consequences of ESS are well known and include: injuries to growth plates, joint abnormalities especially of the shoulder, elbow, hip and knee, and psychological stressors such as burn out. Although growth plate injuries can heal with rest and time off from sport, there may be irreversible changes to the anatomy that may result in growth abnormalities. In fact, a study evaluating injuries in 1,206 17 and 18- year-olds showed how picking a main sport was actually an independent risk factor for injury even while adjusting for age and hours of sports activity per week. Aside from the aforementioned injuries, the following injuries have also been associated with ESS:

- Stress fractures of the hip, pelvis, and spine

- Stress fractures of the foot and ankle joint

- Wrist growth plate injury causing growth disturbances

- Shoulder joint and growth plate injuries causing growth disturbances

- Shoulder joint and irreversible cartilage changes due to an overly focused year-round throwing program

Given the evidence, my recommendation to young athletes, along with their parents and coaches, is to refrain from early sport specialization. Ultimately, I suggest that all young athletes participate in multiple sports and do it for enjoyment, teamwork, and to optimize the comprehensive and balanced development of muscular, joint, and neurological systems in our growing athletes.